(Note: This post covers returns through year-end 2008; for the most recent 5-year return, see this post.)

"Rolling" 5-Year Stock Market (Dow) Returns Graph

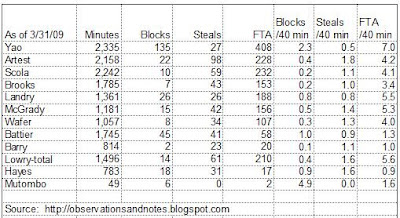

Dow 5-Year Rolling Returns

Above is a chart of the five-year total return of the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average) beginning around 1900. Each point on the graph represents the average annual return earned by an investor who bought the Dow at that year-end and sold 5 years later, reinvesting dividends in the interim. For example, the first point on the graph shows that an investor who bought at year-end 1901, reinvested dividends annually, and sold at year-end 1906 earned approximately 13% per year. As always, I've had to estimate the dividends prior to 1929.

The Best & Worst 5-Year Returns in History

As usual, the worst return (-16.4% per year) resulted from buying before the 1929 crash -- 1927 in this case, rather than our usual 1928. (Note: for more on the 1929 crash, see this post.) Also as usual, the best returns were the result of, in effect, selling near the top of a bubble. Buying in 1923 and selling in 1928 earned a 30.7% 5-year return; buying in 1994 and selling in 1999 earned a 26.8% return. Finally, again as usual, the average return was 10%. (Note: For a very different way of looking at the best and worst five year returns, see Range of Stock Market Returns from 1-10 Years in Dollars.)

Observations & Questions

Not surprisingly, the best 5-year return is better than the best 10-year return, but not as good as the best 1-year return. The worst 5-year return is worse than the worst 10-year return, but not as bad as the worst 1-year return. In addition, while I don't think the cyclicality of the 5-year returns is as pronounced as the 10-year returns, it's clearly more than is visible in the 1-year returns. And, that starts me down a whole new path.

We've been looking at the rolling returns to see what we can learn from them individually. However, there is clearly some kind of a pattern developing if we think of them as a series. For instance, you might ask, as you go from 2-year rolling returns to, say, 100-year rolling returns, what happens to the range of returns? When does the cyclicality start? When does it end? And, what's causing it??

John, thanks for encouraging me to continue this line of inquiry. As a first step, let's take a look at a longer-term rolling return.

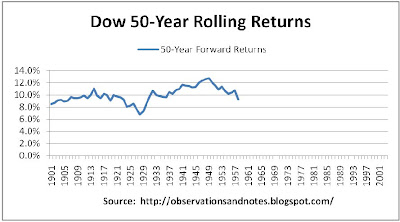

Dow 50-Year "Rolling" Stock Market Returns Chart

Dow 50-Year Returns

The winner is (drum roll please) 1949, with a 12.8% annual return for the next 50 years -- at least partly because, 50 years from 1949 is ... 1999. And, the loser is (another drum roll) 1928, again, with a 6.8% annual return -- for the next 50 years. (Note: The average return was again 10%.) Remember, these are nominal returns, so assuming inflation averaged around 3%, the real return from 1928 was 3.8%. (For more on nominal vs real returns, see this post). As we have seen (e.g., in Stock Market Yearly Returns), investing in the stock market for 50 years exposes you to substantial year-to-year risk. Seems like a lot of risk, and for a lot of years, for less than 4% real return....

I have no idea how you know when you're 50 years before a bubble peaks so that you can buy. But, maybe we have a hope of figuring out when we're already at or near a peak so that we can at least consider not buying.

Let's keep digging.

Note: The above charts are based on DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average) data from my Stock Market Analysis Model. Results would be essentially the same if we used S&P 500 data. Dow dividends prior to 1929 have been estimated using another stock market index.

Related Posts:

See the sidebar to the left for an index of all stock market posts, by subject area -- including:Why Investing in the Stock Market for Less Than 5 Years is Risky: A look at the distribution of the 5-year returns, in dollars.

Range of Returns for 1 to 100-Year Holding Periods graph of best & worst past returns for 1,2,3 ... 100-year periods.

Earnings, Dividends Determine 50-Year Returns: decomposing 50-year returns into return contributed by earnings growth, dividends, change in p/e.

Range of Returns in Dollars for 10-100 Years for a very different look at 50 year returns.

The Best & Worst Years in Stock Market History: 1-year returns

The Best & Worst 10 Years in Stock Market History

The Best & Worst 20 Years in Stock Market History

Rolling 35-Year Returns

Projecting Stock Market Returns

Last modified 8/9/2011